Edge Virtual Bridging (EVB) is an IEEE standard that involves the interaction between virtual switching environments in a hypervisor and the first layer of the physical switching infrastructure. The EVB enhancements are following 2 different paths – 802.1qbg and 802.1qbh. BG is also referred to as VEPA (Virtual Ethernet Port Aggregation); HP has products that are pre-standard VEPA, IBM, Brocade, Juniper and others are engaged and supporting BG. BH is also called VN-Tag; Cisco’s products support VN-Tag today and they brought their solution to the standards bodies. Notably absent from the IEEE discussion of virtual switching is VMware. The two proposals (BG and BH) are parallel efforts, meaning that both can become standards and both are "optional" for any product being IEEE compliant. The standards are likely at least a year from being done in the groups.

Contents |

EVB

EVB looks to solve two common access layer issues:

Looking at a traditional physical access layer we have two traditional options for LAN connectivity: Top-of-Rack (ToR) and End-of-Row (EoR) switching topologies. Both have advantages and disadvantages.

End of Row (EoR)

EoR topologies rely on larger switches placed on the end of each row for server connectivity.

Pros

- Less Management points

- Smaller Spanning-Tree Protocol (STP) domain

- Less equipment to purchase, power and cool

Cons

- More above/below rack cable runs

- More difficult cable modification, troubleshooting and replacement

- More expensive cabling

Top of Rack (ToR)

ToR utilizes a switch at the top of each rack (or close to it.)

Pros

- Less cabling distance/complexity

- Lower cabling costs

- Faster move/add/change for server connectivity

Cons

- Larger STP domain

- More management points

- More switches to purchase, power and cool

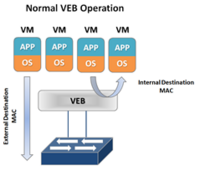

Virtual Ethernet Bridge (VEB)

In a virtual server environment the most common way to provide Virtual Machine (VM) switching connectivity is a Virtual Ethernet Bridge (VEB) in VMware this is called a vSwitch. A VEB is basically software that acts similar to a Layer 2 hardware switch providing inbound/outbound and inter-VM communication. A VEB works well to aggregate multiple VMs traffic across a set of links as well as provide frame delivery between VMs based on MAC address. Where a VEB is lacking is network management, monitoring and security. Typically a VEB is invisible and not configurable from the network teams perspective. Additionally any traffic handled by the VEB internally cannot be monitored or secured by the network team.

Pros

- Local switching within a host (physical server)

- Less network traffic

- Possibly faster switching speeds

- Common well understood deployment

- Implemented in software within the hypervisor with no external hardware requirements

Cons

- Typically configured and managed within the virtualization tools by the server team

- Lacks monitoring and security tools commonly used within the physical access layer

- Creates a separate management/policy model for VMs and physical servers

- These are the two issues that VEPA and VN-tag look to address in some way. Now let’s look at the two individually and what they try and solve.

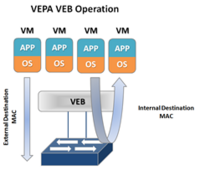

Virtual Ethernet Port Aggregator (VEPA)

VEPA is standard being lead by HP for providing consistent network control and monitoring for Virtual Machines (of any type.) VEPA has been used by the IEEE as the basis for 802.1Qbg ‘Edge Virtual Bridging.’ VEPA comes in two major forms: a standard mode which requires minor software updates to the VEB functionality as well as upstream switch firmware updates, and a multi-channel mode which will require additional intelligence on the upstream switch.

Standard Mode

In the standard mode the software upgrade to the VEB in the hypervisor simply forces each VM frame out to the external switch regardless of destination. This causes no change for destination MAC addresses external to the host, but for destinations within the host (another VM in the same VLAN) it forces that traffic to the upstream switch which forwards it back instead of handling it internally, called a hairpin turn.) It’s this hairpin turn that causes the requirement for the upstream switch to have updated firmware, typical STP behavior prevents a switch from forwarding a frame back down the port it was received on. The firmware update allows the negotiation between the physical host and the upstream switch of a VEPA port which then allows this hairpin turn.

VEPA simply forces VM traffic to be handled by an external switch. This allows each VM frame flow to be monitored managed and secured with all of the tools available to the physical switch. This does not provide any type of individual tunnel for the VM, or a configurable switchport but does allow for things like flow statistic gathering, ACL enforcement, etc. Basically we’re just pushing the MAC forwarding decision to the physical switch and allowing that switch to perform whatever functions it has available on each transaction. The drawback here is that we are now performing one ingress and egress for each frame that was previously handled internally. This means that there are bandwidth and latency considerations to be made. Functions like Single Root I/O Virtualization (SR/IOV) and Direct Path I/O can alleviate some of the latency issues when implementing this. Like any technology there are typically trade offs that must be weighed. In this case the added control and functionality should outweigh the bandwidth and latency additions.

Multi-Channel VEPA

Multi-Channel VEPA is an optional enhancement to VEPA that also comes with additional requirements. Multi-Channel VEPA allows a single Ethernet connection (switchport/NIC port) to be divided into multiple independent channels or tunnels. Each channel or tunnel acts as an unique connection to the network. Within the virtual host these channels or tunnels can be assigned to a VM, a VEB, or to a VEB operating with standard VEPA. In order to achieve this goal Multi-Channel VEPA utilizes a tagging mechanism commonly known as Q-in-Q (defined in 802.1ad) which uses a service tag ‘S-Tag’ in addition to the standard 802.1q VLAN tag. This provides the tunneling within a single pipe without effecting the 802.1q VLAN. This method requires Q-in-Q capability within both the NICs and upstream switches which may require hardware changes.

VN-Tag

The VN-Tag standard was proposed by Cisco and others as a potential solution to both of the problems discussed above: network awareness and control of VMs, and access layer extension without extending management and STP domains. VN-Tag is the basis of 802.1qbh ‘Bridge Port Extension.’ Using VN-Tag an additional header is added into the Ethernet frame which allows individual identification for virtual interfaces (VIF.)

The tag contents perform the following functions:

Ethertype - Identifies the VN tag

D - Direction, 1 indicates that the frame is traveling from the bridge to the interface virtualizer (IV.)

P - Pointer, 1 indicates that a vif_list_id is included in the tag.

vif_list_id - A list of downlink ports to which this frame is to be forwarded (replicated). (multicast/broadcast operation)

Dvif_id - Destination vif_id of the port to which this frame is to be forwarded.

L - Looped, 1 indicates that this is a multicast frame that was forwarded out the bridge port on which it was received. In this case, the IV must check the Svif_id and filter the frame from the corresponding port.

R - Reserved

VER - Version of the tag

SVIF_ID - The vif_id of the source of the frame. *Note*: This format is no longer the .1Qbh format

The most important components of the tag are the source and destination VIF IDs which allow a VN-Tag aware device to identify multiple individual virtual interfaces on a single physical port.

VN-Tag can be used to uniquely identify and provide frame forwarding for any type of virtual interface (VIF.) A VIF is any individual interface that should be treated independently on the network but shares a physical port with other interfaces. Using a VN-Tag capable NIC or software driver these interfaces could potentially be individual virtual servers. These interfaces can also be virtualized interfaces on an I/O card (i.e. 10 virtual 10G ports on a single 10G NIC), or a switch/bridge extension device that aggregates multiple physical interfaces onto a set of uplinks and relies on an upstream VN-tag aware device for management and switching.

Because of VN-tags versatility it’s possible to utilize it for both bridge extension and virtual networking awareness. It also has the advantage of allowing for individual configuration of each virtual interface as if it were a physical port. The disadvantage of VN-Tag is that because it utilizes additions to the Ethernet frame the hardware itself must typically be modified to work with it. VN-tag aware switch devices are still fully compatible with traditional Ethernet switching devices because the VN-tag is only used within the local system.

Reference: See Joe Onisick's blog post Access Layer Network Virtualization: VN-Tag and VEPA

Also see this Feb '12 update from Ivan Pepelnjak on his IPspace blog